Recent Reviews

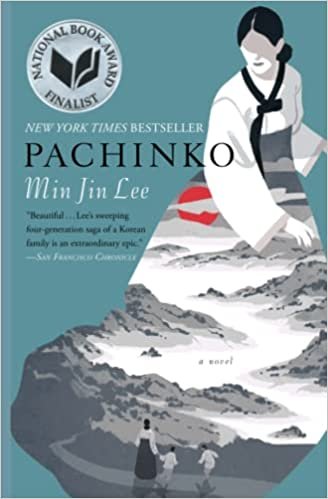

Pachinko by Min Jin Lee

In her exceptional debut historical novel Pachinko, Min Jin Lee follows four generations of a Korean family. It is a heart-wrenching and soulful story about how family members endure and adjust to the colonization of Korea by the Japanese in 1910, their immigrant status in Japan, and the subsequent division of their homeland after WWII. The book also probes family dynamics as each individual wrestles with his or her new identity as a Korean immigrant contending with racism and discrimination by the Japanese.

Hoonie and Yangjin, a poor couple living in a fishing village on the southern tip of Korea, have a daughter named Sunja. When Sunja is in her teens, she meets a married man, Hasan, and becomes pregnant. Hasan offers to provide for Sunja and their son, but Sunja does not want the life he offers. Sunja’s mother speaks to a minister who is moving from Korea to Japan. Despite her pregnancy, the kind minister asks Sunja to marry him, allowing Sunja and her mother to escape the shame and humiliation of Sunja’s illegitimate pregnancy.

Sunja and her new husband Isek move in with Isek’s brother and his wife in Osaka, Japan where they face occupational limitations. As Sunja’s oldest son grows, he sees being Korean as “a dark, heavy rock." His greatest, secret desire is to be Japanese. Sunja’s younger son’s girlfriend wants to move to America. “To her, being Korean was just another horrible encumbrance, much like being poor or having a shameful family that you could not cast off. Why would she ever live there? But she could not imagine clinging to Japan, which was like a beloved stepmother who refused to love you, so Yumi dreamed of Los Angeles. There, no one would care that we are not Japanese.”

Sunja’s sons eventually operate Pachinko parlors in Japan, a permitted occupation for Koreans. Similar to pinball, the balls bounce around the Pachinko machine and land in random locations. And like life, Pachinko players must make decisions based on where the balls land even if the game is rigged. For Koreans, getting ahead is nearly impossible irrespective of how hard they work. The Japanese limit their opportunities and then ridicule them for not rising in the Japanese social hierarchy - a predictable pattern in systemic racism.

The family members labor and suffer but remain devoted to one another as they adapt to their changing circumstances. They experience joys and triumphs as well as despair and pain. Lee elucidates the superstitions and traditions that serve the family well and cause them to suffer. As Lee states in the opening line, “History has failed us, but no matter.” Min Jin Lee, however, succeeds in writing this epic family story that illuminates how one Korean family perseveres beneath the weight of prejudice and pain.

The Ocean at The End of The Lane by Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman’s award-winning 2013 novel The Ocean at the End of the Lane feels like a combination of C.S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia, J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, and The Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Using vivid imagery and rich allegories, Gaiman creates a story that is part parable, part fantasy, and part psychological portrait. This short engaging novel challenges readers to contemplate and interpret the events described.

On one level the book is straightforward: a nameless middle-aged man returns to his hometown of Sussex, England to speak at a funeral. After the funeral, he finds himself in the home of his only childhood friend, Lettie Hemstock. His initial memories are vague. “But standing in the hallway, it was all coming back to me. Memories were waiting on the edge of things beckoning to me. Had you told me I was seven again, I might have half-believed you, for a moment.”

His seven-year old self narrates the bulk of the book and many possible interpretations emerge. First, his beloved cat is killed and then the family’s boarder kills himself. Soon after, his mother return to work and a new boarder, Ursala Monkton, arrives to care for the young boy and his sister. The woman is cruel and mean. When the boy then shows disrespect toward Ursala, the boy’s father submerges the boy in the bathtub. Soon he sees his father and Ursula kissing in the living room. The culmination of these occurrences leads the boy to feel that an evil spell has been cast upon him. The innocence of this lonely, thoughtful child is shattered.

Scary and spooky phenomenon begin to occur and the seven-year old boy feels frightened. The story combines actual life incidents with supernatural battles between good and evil creatures. Is this precocious boy dreaming? Did all these events occur? Or is he creating narratives in his head to defend against his new knowledge of cruelty, adultery, and death?

As kids grow up, they make sense of confusing or traumatic incidents by creating narratives that mix fact and fiction. Fuzzy images and events from childhood can lurk within. The unconscious can repress memories until a child is ready to confront the event or feeling. As the narrator describes beautifully, “Childhood memories are sometimes covered and obscured beneath the things that come later, like childhood toys forgotten at the bottom of a crammed adult closet, but they are never lost for good.”

Lettie Hemstock tells the young boy, “Grown-ups don't look like grown-ups on the inside either. Outside, they're big and thoughtless and they always know what they're doing. Inside, they look just like they always have. Like they did when they were your age. Truth is, there aren't any grown-ups. Not one, in the whole wide world.”

This realization illuminates and disappoints the boy as it suggests the judgment of adults is not to be trusted, but at least Lettie's comment corroborates his recent experiences. Gaiman’s perceptive novel penetrates this complex process of maturation and engenders empathy and understanding.

House of Sand and Fog by Andre Dubus III

The House of Sand and Fog is probably best read in December when the darkness of the month matches the darkness of this gripping story. This novel by Andre Dubus III was a National Book Award finalist in 1999. Dubus captures the characteristics, values, and motivations of each of his three protagonists. He provides compelling back-stories and psychological nuance for each of these characters. I felt frustration and anger as well as understanding and empathy as each character made choices that I knew were not going to end well. As my grandmother used to say, “We are all prisoners of our personalities.”

Dubus’ book also illuminates the ongoing culture clashes between immigrants and those who (erroneously) perceive themselves as indigenous Americans. Massoud Behrani is a former colonel in the Iranian Imperial Air Force and was forced to leave Iran after the overthrow of the Shah. Once in California, he drives a fancy car and dresses in a suit when he leaves for work. But then he parks the car and changes his clothes to collect garbage by day and clerk at a convenience store by night. He must maintain the impression that he is still affluent to his fellow Iranian exiles. When he sees an ad for "Seized Property for Sale," he purchases a three-bedroom ranch house with his meager remaining funds. Filled with hope, he and his wife and teenage son move into the home. Behrani intends to improve the house and resell it for a profit. The house symbolizes the beginning of his new successful life in America.

Unfortunately, the house was improperly sold due to a bureaucratic error by the county. The rightful owner of the house is a troubled young woman named Kathy Nichols who works hard at being a waitresses and keeping away from drugs. For her, too, this little bungalow, with a distant view of the Pacific Ocean, represents stability. When Kathy Nichols drives to the house to confront Colonel Behrani, Sheriff Lester Burdon is called to the scene. Before long, Sherrif Burdon falls in love with Kathy and becomes obsessed with helping her to get her house back. (A little cliché, but it works.)

When the county offers to return the Colonel’s money, he refuses. He is a man who is accustomed to getting what he wants and he wants the house. As the days and weeks pass by, Kathy and Behrani think of little else. Neither will give in. Their thoughts and behaviors become focused and narrow. It is as if they are in a tunnel from which they cannot escape. Kathy and Behrani both perceive that ownership of this house will provide solidity and stability to their lives. Their rigidity prohibits them from understanding each other’s perspective. There is tenderness when Kathy Nichols and Mrs. Behrani interact, which made me feel hopeful that the conflict could be resolved. But, not surprisingly, the terms of engagement seem dictated by the men and my hope soon faded. The Colonel’s obstinacy sets the tone and is a catalyst for the tragic chaos that ensues. Like characters in a Shakespeare play, Dubus’ three characters pass a point of no return where they abandon rational thought and make choices that lead to dire consequences. As Colonel Behrani says, “For our excess we lost everything.”