Recent Reviews

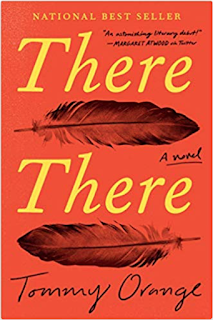

There There by Tommy Orange

Review published in the San Francisco Examiner on October 28, 2018

http://www.sfexaminer.com/oaklands-urban-indians-come-life-exquisite/

Tommy Orange’s There There has been a Bay Area bestseller for a reason. His novel is exquisitely wrought and tells the story of twelve characters who plan to attend a “Big Oakland Powwow”. They are not traveling from rural reservations. As Orange says, they are “Urban Indians” who call Oakland home. They live in a cityscape where BART stations, the Oakland Coliseum, and the Grand Lake Theater mark the terrain.

The book’s title is borrowed from Gertrude Stein. When her Oakland home was torn down and her old neighborhood redeveloped, she observed that the “there” of her childhood had ceased to exist. As one of the novel’s characters, Dean Oxendene states, “But for Native people in this country, all over the Americas, it’s been developed over, buried ancestral land, glass and concrete and wire and steel, unreturnable covered memory. There is no there there.”

Orange begins this uniquely structured book with a prologue recounting the cruel history of efforts to eradicate the Native American peoples. He describes the betrayal and brutality that the Native Americans endured as they negotiated with successive waves of Europeans including the Pilgrims. He reminds us how violent a history it has been.

Each subsequent chapter is the story of a single character. We learn their histories and hopes, their strengths and sorrows as they prepare for the powwow. They each have their own reasons for attending - some practical, some profound. Orange writes, “We made powwows because we needed a place to be together.” Many of the characters work at the Indian Center. They struggle with alcohol, drugs, poverty, mental illness, violence and shame. We meet Tony Loneman who was born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. We meet Orvil, Loother, and Lony Red Feather whose mother committed suicide. We meet Calvin Johnson who is bipolar and whose brother is a drug dealer. Each of the character’s stories is emotional, raw and intimate. As we learn about them we understand why their lives are so difficult. Orange points us to a James Baldwin belief, “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

Yet, these characters are not as bitter as one might expect, though most live on the edge. Rather, they navigate their present lives while carrying the psychic pain of their ancestors’ suffering. These Urban Indians persevere and find their own unique ways of expressing their Native heritage in Oakland.

The characters vary by tribe, age, gender and attitude. About their collective past, they have different interpretations. They voice fervent beliefs and existential observations. Tony Loneman says of his ancestors, “They must not’ve had street smarts back then. Let them white man come over here and take it from them like that.” Another character Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield says, “Don’t ever let anyone tell you what being Indian means. Too many of us died to get just a little bit of us here, right now, right in this kitchen.”

Orange weaves together these individual stories as the plot plays out in surprising ways at the powwow at the Coliseum. The Natives have come to dance, celebrate, sell crafts and just be together as Natives. But a few of the characters have nefarious plans. Violence lurks, the dancing ends, and the powwow crescendos to a chilling climax.

Tommy Orange’s book is a literary burst of pain and rage leavened by understanding and empathy. Orange has reimagined and updated the story of the Native people of our country. He has a sympathetic ear for the psychological burden that the past brings to the present. There There is the work of a talented and urgent new voice on the literary scene.

Secrets and Shadows by Roberta Silman

Roberta Silman’s Secrets and Shadows adds another important narrative to the numerous novels about Jewish families who endured the crazed cruelty of the Nazis during WWII. The novel also illuminates how fast democratic norms can be diminished until they erode completely leaving anarchy and evil in their place.

When the Berlin Wall falls in November of 1989, Paul Bertram calls his ex-wife Eve and asks her to accompany him to Germany. Given their almost non-existent communication, the request baffles Eve but she nonetheless agrees to join him.

As they visit the Berlin landmarks of Paul’s childhood, Paul recounts the incremental loss of freedom he and his family experienced in the 1940s. As a boy, Paul was known as Paulie Berger. His family was Jewish and his father owned a jewelry store. When it became clear that leaving Berlin was not viable, Paul’s parents arranged for a Gentile family, with whom they were friends, to move into the Berger’s home. The Berger family, in turn, moved into a hidden room in the attic. As the Nazis crept closer, the Berger family fled to the forest. Before their departure, Paul made a spiteful decision that affected the Gentile family. He had never told anyone - until this trip.

Paul had immigrated to the United States and became quite successful. He attended college and law school, married his wife Eve and became the father of three children. Yet internally, he felt ashamed about the choices he made as a teenage boy. The psychological trauma of his wartime experiences stayed with him. The accumulated stress and guilt haunted his every move. Paul withdrew from his family, flew into wild rages and engaged in a series of public affairs. Finally, Eve and Paul divorced and retreated into separate lives.

What Eve learns about Paul’s boyhood experience shocks and saddens her. She had never pressed him for details during their marriage. She feared what she might hear. Now she understands that Paul’s emotional distance came from the horrors he witnessed and his need for self-punishment. For Paul, the trip is part confessional, part therapy and part detective work to answer his own questions about those years. A unique aspect of this novel is that Paul is able to return to his boyhood home and even encounter one of the people he had betrayed. His psychological healing may begin.

The structure of this novel feels disjointed and the prose can ramble. Nonetheless, it is another significant story of the inhumane treatment of Jews during WWII. These stories, fictionalized or not, must be known and heard. Though Paul and his family escaped the concentration camps, they experienced their own version of hell. Secrets and Shadows shows how unspoken trauma can reverberate through families. The novel also reminds us that even when good people band together to confront evil, sometimes it can be too late.

Fruit of the Drunken Tree by Ingrid Rojas Contreras

Review published in the San Francisco Examiner on September 9, 2018

http://www.sfexaminer.com/tag/fruit-of-the-drunken-tree/

Fruit of the Drunken Tree is a riveting new novel by talented Bay Area writer, Ingrid Rojas Contreras. It is a powerful and disturbing coming-of-age story set in the Bogotá, Colombia of the 1990s. The book describes the intersecting lives of two young girls, one affluent, one poor, trying to grow up as a cyclone of escalating violence engulfs them. Kidnappings, assassinations, car bombs and the pursuit of Pablo Escobar punctuate their daily lives. The book is ultimately a tale of emotional resilience, as these children come to terms with the frightening disintegration of civil order.

Seven-year-old Chula Santiago lives in Bogotá with her nine-year-old sister Cassandra and her mother and father, Alma and Antonio. Inside her guarded community, Chula lives in comfort, plays with dolls and watches Mexican soap operas. But the threat of violence hovers all around. Anxiety is her constant companion. She tells us early on, “Most people we knew got kidnapped in the routine way: at the hands of guerrillas, held at ransom and then returned, or disappeared.”

Chula’s father works for an American oil company and is often away from home. Chula’s mother hires thirteen-year-old girl, Petrona Sánchez, as a maid. Petrona lives in abject poverty in an invasión, a slum on the outskirts of Bogotá. Her mattress rests on a dirt floor, there is no running water and food is scarce. A paramilitary group had kidnapped her father and older brothers and torched the family’s farmhouse. Petrona now provides for her mother and remaining siblings as best she can.

The narration of the novel rotates back and forth between Chula and Petrona as they absorb each new event in this dystopian world. The girls attempt to learn the names of a bewildering array of drug lords and guerrilla groups. A confused Chula says, “…I couldn’t grasp the simplest of concepts—what was the difference between the guerrillas and the paramilitary? What was a communist? Who was each group fighting?” The girls are living in a war zone. When Petrona becomes involved with a young man who has joined a guerrilla group, Chula and the Santiago family are suddenly more vulnerable.

A foreboding sense of danger and death lurk on every page. As societal norms erode and the poor grow desperate, some people’s behavior become more depraved. The young girls attempt to make sense of the mayhem from their separate perspectives. When Pablo Escobar is captured, Chula’s sister says, “We can go to the movies! We can go out wherever we want now and we won’t have to fear being blow up!” Petrona views it very differently, “People like el Patrón where I’m from.”

Rojas Contreras masterfully places her fictional characters into the real historical events of that tragic time. Her language is rich and beautiful and she deepens our immersion by blending Spanish words and phrases into the story. Like an Isabelle Allende or Gabriel García Márquez novel, Fruit of the Drunken Tree includes captivating moments of magical realism.

By the time the Santiagos flee Colombia, Chula has personally experienced many violent incidents. Not surprisingly, there is a severe psychological toll. Chula’s panic attacks increase and PTSD dominates her daily life. The Santiagos eventually liquidate their assets and leave Colombia for California. But, it is clear that no family member will be able to leave the trauma behind. Petrona has her own scars, but no such possibility of escape.

It is almost too painful to imagine children growing up in this environment, but all too many did. Rojas Contreras was one of them, a testament to her resilience and strength. Many of the events described in this heartbreaking novel are based on her own experience. She does not seek to assign blame for the chaos in Colombia; rather her impressive novel engenders empathy for the children who were robbed of their childhoods.